My New Blog Address

October 6, 2011 § 11 Comments

From now on my blog address is tracycochran.org. I am very grateful to everyone who reads and subscribes. Please find me at my new address. Until soon!

Harry and Jane

October 3, 2011 § 25 Comments

We are hard at work, pulling together a new issue on the many paths people take to find truth, and the articles in this particularly lively issue range from sacred music to the spiritual home that is Harry Potter.

Lately, I find myself pondering the similarity between Harry Potter and Jane Eyre. Jane, as some of us may remember (and as I am rediscovering) was an orphan who is grudgingly taken in by a resentful and nasty aunt. Little Jane is as viciously bullied by a fat spoiled cousin John as Harry was by Dudley, and is as wretchedly excluded and unloved by the whole family—she listens to Christmas parties while shut up in a little cupboard with only a doll to love. By her own admission (told many years past childhood), Jane isn’t as sweet or as loveable a child as little Harry. She is completely opposed to her adoptive family, “incapable of serving their interest, or adding to their pleasure; a noxious thing, cherishing the germs of indignation at their treatment….”

She doesn’t receive an invitation by owl that affirms what she knows in her heart to be true, that she is indeed very different than those around her. She is not whisked away to Hogwarts but to a wretched school called Lowood. And yet she finds in the depth of her misery, a spirit and a self awareness and self-acceptance that work a kind of magic. Banished to boarding school, abused beyond all endurance, she at last confronts her aunt as children never did in the Victorian age, calling her bad and hard-hearted.

“Ere I had finished this reply, my soul began to expand, to exult with the strangest sense of freedom, of triumph, I ever felt. It seemed as if an invisible bond had burst, and that I had struggled out into unhoped-for liberty.” Even though Jane later feels that this act of vengeance was like a sweet but poisonous wine, it is as necessary to her future development as Harry’s rollicking escape from his tormentors with its dash of sweet revenge.

As Jane’s nurse Bessie tells her, at least some of the scolding that comes to her is “because you’re such a queer, frightened, shy little thing. You should be bolder.” If you cringe and dread people, if you hide yourself “they’ll dislike you.” Jane and Harry both have to learn to affirm and express themselves.

“You have to be someone before you can be no one,” this statement is repeated in Buddhist circles, and it is equally applicable in Christian, yoga, Gurdjieffian or any other kind of circle dedicated to inner development. It seems like the biggest paradox. If the goal of spiritual life is to be liberated from a sense of separation from life, why value separating, becoming individuals? Why not stay in the cupboard and skip straight to transcendence?

What is the value of affirming a self, identifying the life force as our own—of getting out there in the world and proclaiming ourselves and struggling and trying? We need to really be ourselves, to really live without holding back, or nothing can really be known. Transformation is not a thought. It is a drama that must be lived. Also–and I’m really interested in what you think of this–I’ve heard it said that holding back, being timid, not daring to step up and show ourselves and be responsible, is really a kind of negative conceit. What do you think?

Be Your Own Angel

September 26, 2011 § 39 Comments

Will and Grace

September 21, 2011 § 6 Comments

Last week I wrote about the experience of being lost in the woods around the Garrison Institute on the banks of the Hudson. Someone commented that I were never truly lost, and this is true: we wandered just far enough off trail to have a nerve-tingling, sense-heightening experience of waking up from the dream of knowing who we are and where we are going. It was a shock, and shocks have a way of posing big questions like “Who do you think you are?” and “Where do you think you’re going?” Shocks have a way of showing us what we are made of–not just in the usual sense of revealing character traits like good humor and courage or the opposite, but that we are made up parts that don’t quite mesh–we can be brave in one way and timid in another. And at any rate, we don’t add up to an inviolate whole.

The Buddha compared people to chariots, and this analogy is very significant because it turns out that the Pali word “dukkha,” which is usually translated as suffering really means something like “bad wheel” and it refers to the hole in the hub that often got clogged with dirt and grease so the wheel didn’t turn quite smoothly–so there was always a slight bumpiness or unease: life is dukkha means that life rolls along in a way that is always a little less than smooth for us chariots, always a little bumpy and anxiety-provoking. Gurdjieff compared people (at least those who tried to see themselves) to cars with their hoods up–the point was not only that we are actually a collection of parts but this mechanism is not a pretty or smooth-running sight when you see it up close (unless you are a skilled mechanic). When I was lost I had a glimpse of this situation–that we are made up of parts like cars and chariots and these parts don’t purrrr along in perfect harmony with each other and the world around us. I triggered a surge of energy, a definite sense of being here and now. And now I’m reflecting on the experience of being found.

In Buddhism, the experience of mindfulness or “sati” (which literally means remembering) refers to a sky-like state of awareness. Mindfulness can include everything that arises, inwardly and outwardly. At different moments and in different instances, however, mindfulness may reveal different aspects or qualities. One factor is investigation, which is that probing quality of attention that arises, say, when are lost in the woods and seeking the path–in classical Buddhist terms, it refers to investigating the way things are and the way things happen, the lawful unfolding of things. Another factor is energy, which was referred to in anciet Sanskrit and its street variant Pali by the word “virya.” In the Rig Veda and other ancient Sanskrit texts “virya” referred to a hero, one who was virile (you probably guessed that). As in many other instances, the clever, radical Buddha recast or liberated this word to mean the special energy and effort it takes make the journey to liberation.

We still need to be heroes, but the quality of the effort required isn’t so, well, effortful. It has to do with opening to what it is, to letting be. I’m about to make what might seem to be a wild leap, but this is the fun of blogging and I do have a point, so please stay with me. Towards the end of his journey, Hamlet becomes at last reconciled to his particular tragic situation. His friend tries to talk him out of accepting the challenge of a duel that both sense is a trap. But Hamlet has come to understand something profound about the nature of reality–that we really are not in control in the way we dream we are:

“If it be / now, ‘tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be /now; if it be not now, yet it will come. The / readiness is all.”

Hamlet came to see and accept that reality was determined ultimately by a greater lawfulness, by God. He came to see that our true freedom, our true sense of place and empowerment comes from letting go of our own will (Shakespeare knew a Bible that uses “readiness” for “willingness”) and being willing to take our true place. We find ourselves, our true purpose and path, as we learn to stop leaning forward, effortful and anxious–when we fall back on God.

Lost in the Woods

September 13, 2011 § 19 Comments

Last week, I was at the Garrison Institute in the Hudson Valley, experiencing another retreat in Spirit Rock Meditation Center’s “Community Dharma Leader Training.” Why an editor of Parabola would undertake such a training, what I have learned so far and what I hope to gain–the Parabola sangha I hope to create–I’ll be getting into that in the weeks to come. For now, I would like to describe how I managed to get lost in the woods.

It rained for days. The beautiful former monastery had begun to feel a bit like a gloomy English boarding school, and I had begun to feel a bit like Jane Eyre, doing my best to keep my chin up and my spirit alive. Finally, there was a break in the weather and many of us went outside. As stood there, feeling a bit lost and lonely (as one does at times on retreats) a friend came up. “I’ve found the path you’ve been looking for,” she said. She was referring to a conversation we had the first day, when we were both looking for a walk in the woods. I knew this. Yet, in the container of the retreat hearing “I’ve found the path…” was irresistable. I set out after her. We hadn’t gone far when we picked up a third hiker, also looking for the perfect path.

It was glorious, the perfect path through the woods, complete with a waterfall and tumbled down rock walls. As we walked, we talked about life and about our lives…and the next thing we knew we had lost the trail and we were lost. It was fun at first, and then we really couldn’t find the trail and we grew a bit frightened. We worried that we would miss dinner, which is a huge source of comfort on retreat. We fretted that the retreat organizer would have to call for volunteers with wildnerness skills to come looking for us. I wondered about using the GPS app on my phone as a compass.

“Not until we are lost do we begin to understand ourselves,” said Thoreau. This was another one of those times when the trance of the ordinary was suspended. My true vulnerability, my true lack of connection to the real world was suddenly painfully exposed. It was glaringly clear that I live mostly in my head and that I have very little in the way of practical knowledge. I saw that I am a collection of parts not a whole, and that these different parts are often pulling in opposite directions, driven by different motives. And yet I saw that this very act of seeing, this opening to what is, called up—literally recalled–a different quality of understanding and intention. A more spacious quality of awareness appeared that was quicker and more sensitive than my usual thinking. I didn’t magically become an expert tracker–it was my companion who found the trail–but I felt as if I was assuming an inner attitude—a way of being with life–that was more whole, more deeply human than the way I usually operate.

Not only did I feel that body, heart, and mind were more aligned and working together, I felt the three of us start pulling together. I’ve written before about noticing a glow inside, the glow of our own life force and our own capacity for awareness. I’ve written that it can seem very faint, like a candle or a nightlight. But when I was lost in the woods around Garrison Institute, I discovered–or rediscovered–how we can pool our light and find our way.

After I made it safely back to the dining hall (and in time for dinner), I reflected on how important it is to have a journal and a community like Parabola–a place where people who are walking different paths or searching for a path can come together and have an exchange about what we have found. Due to forces and conditions beyond the control of our loyal band, we are struggling as never before. Please consider subscribing or make a tax deductible donation so we can continue to publish and become the sangha we know we can be.

Irene Lessons

September 1, 2011 § 14 Comments

In the wake of Irene, we lost power for four days. For days, I collected sticks in the yard to burn as kindling in the wood stove, and hauled buckets of water into the house to flush the toilet and wash the dishes. It was strange, being so cut off in one sense yet feeling so intimately connected with life and with the way much of the rest of the world lives. Instantly, I was aware of how precious clean water is, and how much I usually waste. Suddenly, I became aware that a house grows dark and cold at night without someone to build a fire and tend it. I became the fire builder, the keeper of the hearth. Anthony, my daughter Alex’s boyfriend from England, cooked food on the cast iron stove. We all learned how long it takes to cook over a fire—hours! And yet this was the center of the evening, the light and warmth from the fire, the promise of warm food, the common talk of how it was coming along, and then storieswe told as we ate. We all learned what is elemental and crucial, and that these basic things can be hard work, yet there is something inherently good and right about it. All beings deserve to eat and be warm and safe, and being mindfully engaged in this work can bring wisdom about life. (For starters, a couple of highly educated young people here learned a little something about what it takes to build a good fire).

As the third day dawned to no hot coffee or tea (unless I got up and built a fire and waited for three hours), it began to feel like an ordeal. Alex was sick with a bad cold, our water supply was almost exhausted–and I discovered that those little moments of good humor—that impulse to forget ourselves and help someone else are as crucial fire. On the third night, as I was struggling to light a fire with damp kindling, the neighbors came by with big pales of fresh water: “We wanted to give you the gift of being able to flush the toilet,” they said.

Another neighbor came by and asked from my email address so she could forward updates about the progress of repairs and availability of water to my iPhone. I saw how technology can help in crucial and elemental ways. I also marveled at the way this common humanity–this pulling together–just arose spontaneously. We innately know we can’t go it alone. We neighbors who rarely have the chance to stop and talk stood outside together laughing and talking. We even looked up at the stars that we commented were so clear without ambient lights…and…

And we marveled together at the roar of some of our other neighbors’ gas generators! “It sounds like a carnival!” said one woman. And it did! It sounded like the county fair, with all the motors that power ferris wheels and who-knows-what—and all of that sound and all of the gas that went into it to keep their refrigerators pumping and the ice cream frozen and the laptops charged. “This whole experience would have a different quality without that din,” she said. And I’m not pretending to be Thoreau. I took several long drives (dodging downed power lines and trees!) to charge my laptop and iPhone at a friend’s house and take a shower. And yet, I came away from this experience knowing body, heart, and mind that we don’t need to use as much energy as we think. I glimpsed how life can actually be richer and better with less.

When the power came on (bringing a blessed silence), I took a long hot shower, realizing moment by moment what a pleasure and luxury it is to have such a thing. I wondered how long I would remember to be aware of this. I washed dishes and cleaned for hours, experiencing it as a luxury, aware that by the standards of history and the world today, I am very privileged. Alex and her boyfriend left the house to go shopping for college (street lights! No danger of fallen trees and wires and flooding in the dark!) And when they came home the house was bright and cheerful. Instead of gathering around the fire, they took to their laptops, and I took to my bed for a bit of CNN and a book. Witnessing ravaged areas here and abroad, I felt blessed.

May I remember what I learned about the preciousness of water and warmth and helping our neighbors. May I not use technology to go numb.

Waiting for Irene

August 26, 2011 § 8 Comments

Like many people in the greater New York area, I am preparing for Irene. I was up early cleaning and tidying up and doing laundry—the prospect of power outages lasting for days and flooding and apocalypse makes a person want to start out as clean and neat as possible. A few days from now, I might be cooking beans and smoked sausages over a fire bowl in the yard, wearing rubber boots. We just don’t know, and that’s a very interesting place to be. My daughter’s boyfriend is visiting from England—first trip to New York–and in less than a week he will have experienced an earthquake and a hurricane. We like to show our out-of-town guests a really interesting time.

We’ve been talking about solitude and community in this space, about what times or conditions allow us to feel fully alive and aware—that can even sometimes allow us to resonate with a sense of the Whole. As I was bustling around making preparations this morning, I thought of all the other people up and down the I-95 corridor who were doing something similar. I thought of those haunting reports of the animals fleeing the tsunami before it came, relying on some mysterious ability to sense or feel that we have lost or never had. Stunted as we are compared to them, however, situations like this do awaken a bit more presence. Preparing for basic survival, storing water, stacking firewood, will do that.

One thing that can be said about a hurricane isthat you know you aren’t in it alone. You feel connected to not just to the people facing this storm now, but to people in all times who have faced storms, who have faced the unknown. Times like these are really interesting opportunities to watch the mind. We think we know how to prepare as well as we can and then let go and let God as they say. But we really actually tend to think ahead and try to control outcomes–try to think our way past things–all the time. We can’t help it. We are story-spinning creatures, and we want things to turn out well. While we’re waiting and while we still have power, let me tell you a little story about this.

When my daughter Alexandra was four or five years old (she is now 21 and thinks I’m making too big a deal about the hurricane), we lived in Brooklyn, and it was the custom to put things out on the street for others to take (as it is in many places). When Alex outgrew her little bicycle with training wheels, I encouraged her to give it away. She made a sign that said “Free bike! Please enjoy” in purple crayon, and we taped it to the bike and carried the down the wide steps of the brownstone one last time and set in near the curb. It felt so freeing for both of us to leave it sitting there in all its sparkly purple glory, no lock and chain. I told her that giving things away can be as wonderful as receiving. I told her that the universe works in mysterious ways and that giving actually gives us something in return.

The next morning she clamored down the ladder of her loft bed and ran to the big living room windows that overlooked the street. “The bike is gone!” She exclaimed with a smile I associated with Christmas morning. I told her that was wonderful, and we beamed at each other. “Now when do I get something back?” she asked.

Most of us are like this. We move from hope to hope, from fear to fear. This is perfectly natural. We want to be safe and happy. Many of us are good-hearted human beings who other beings to be want to be safe and happy. But we really need to open up what we take real happiness to be. The Middle English root of the word “happiness” is “happ,” which means fortune, chance, happenstance, what happens. In virtually every Indo-European language the root is the same. It is built into the language and perhaps our genes to equate happiness with what happens to us.

Yet no matter how well you plan or how privileged you are, things happen that are outside your control. There really is no higher ground, no absolutely safe place to stand. My dear departed mother always told me to remember that no matter how rough a hurricane is (and my mother lost a house and a beach-side condo in a hurricane one year) it is always the poorest among us always suffer most: “They don’t have much to start with and then they lose that.” (When I asked my mother if she didn’t mind losing so much herself she said she could stay in my sister’s nice house while she rebuilt. “And I’m too old to cry over things.”)

And yet we are all subject to the same forces. The ground is moving under all our feet. Without denying the reality of injustice (even in this storm some will suffer far more than others–and may all be safe and well), I’m beginning to realize that the only real source of security and happiness we have is touching the earth of our common human experience. There is no escape from our common human situation; there is only healing, only helping, only grace. There is only participation.

Blessed are those who know they have no answers, who have empty hands, for they may be given something—including something practical to do to help others. There is a light inside each of us that doesn’t depend on outside circumstances. We don’t tend to notice it when things are going well. It can seem like little more than a faint glow, which may be why it is most visible in a state of inner stillness or in the midst of widespread power outages. A person wouldn’t notice a night light in full sun, would they? But a small light can illuminate the darkness (as many of us in the I-95 corridor will soon know).

Certain kinds of suffering, including waiting and uncertainty, can give you the feeling of resonating with the Whole, with other beings and with the earth itself. These situations also have a surprising intimacy about them, a kind of open solitude. They help you touch another source of understanding and intention, something deeper than our ordinary self-centered and socially conditioned minds. As tiny and undeveloped as it may sometimes seem, there is in each of us (or most of us) a deep wish to be part of life and a capacity to resonate with it, to understand. Remember what has come to life in you at times when there was an emergency, times when you had to “snap out of it.”

Smirti in Sanskrit, sati in Pali, and Drengpa in Tibetan. All these words mean to remember. They point towards a kind of understanding that isn’t thought up in the head but lived through (stood under, like standing in the rain and letting it soak in). This kind of remembering means to “re-member” or “re-collect” and it means having the head and heart and body all in alignment, all present and participating together. To have real presence means remember what it means to be fully human. It means gaining the power that comes with coming out of our isolation and joining the whole human race. This seems a pretty good way to prepare for a hurricane. Although it’s good to have batteries and drinking water and a few other things as well.

Wish us luck! I’ll let you know how it goes.

Feeling the Earth Move

August 23, 2011 § 9 Comments

As I was writing this blog on my laptop—which happens to be about how oblivious we usually are to our interconnection—the sofa started to shake. “Earthquake,” I thought, suddenly really aware that I was in was on the earth and that it was trembling beneath me. I thought of the earth shaking in recognition of the Buddha’s awakening. It was as if the earth knew that Buddha was awake and fully perceiving its life.

“It is fairly obvious by now that life on earth forms a vast interconnected and interdependent network,” writes Christian Wertenbaker in the “Seeing” issue of Parabola. This really has become general knowledge. Most of us accept (however grudgingly) that we live inside an ecosystem—and that we ourselves are ecosystems: just as birds keep a hippopotamus clean, intestinal bacteria help us digest. We are used to hearing by now that the building blocks of life—carbon, oxygen, nitrogen and the rest—“were formed in the nuclear furnaces of stars and distributed by the explosions of supernovae, as part of vast cosmic cycles of stellar formation, growth, and death.”

We are deeply embedded in life and we are made to participate in life. Most of us get this, yet Wertenbaker reminds us that something more is possible. We are also capable of resonating with (and therefore discovering) the underlying mathematical forms or laws of reality. Wertenbaker draws on Gurdjieff who draws on a very ancient idea: By perceiving consciously instead of in our usual state of unawareness “we are, or can be, part of a great cosmic ecology of consciousness….” Just as our bodies are made of atoms, our inner life in the form of our conscious perceptions and reflection connects us to the Whole.

Many of us resonate with this. Yet many of us treat having an inner life as a solitary pursuit, something we keep to ourselves. Is that not strange? I wrote last time about being young and learning that it was best to be a kind of secret agent, to keep my innermost thoughts and perceptions to myself, to keep my vulnerability hidden under a cloak of cool (or at least an attempt at cool). None of this is unusual in this culture. Nor is the love I had of outlaws who were secretly pure and innocent—from the Kerouac to Count of Monte Cristo (who was intent on revenge for his wrongful imprisonment, but that’s another story). This is a pretty standard part of growing up. But it is also intensely ironic, because even these romantic figures (certainly Kerouac) were seeking a sense of interconnection and resonance with higher laws.

Solitary as the spiritual search might seem, there inevitably comes a moment when I find myself sitting with in a shadowy hall somewhere. Wrapped in shawls or yoga blankets, sitting still with backs straight on cushions, we look like the earliest humans, at least as I imagine them. Or maybe we just look like earliest humans in the sense of being like children again, facing life with our whole beings. At those times, I know that for all my shyness, all the defenses I have picked up over the years, I am still capable of real connection with the others, all of us coming so far to be together—and not just New York and California but through all kinds of difficulties. And all of that common effort made just to risk trying for greater awareness–for a consciousness that isn’t attached to memories and feelings and views, that isn’t separate from life by being attached to being a particular “someone” who needs to be defended.

“There is no way out; there is only healing,” a teacherwho really knows what she is talking about said to me. There is no escape from our situation. Everyone has their reasons, their wounds. There is nowhere to go but down into our common humanity. There usually comes a moment when I am sitting in a room full of fellow humans, all of us drawing our attention to the breathing (among the most basic and easy to track exchange with the outside world), when we can feel like we are descending into a vast subterranean cave full of forces and energies unknown to the ordinary thinking mind with its obsession on protecting and defending.

When I go on retreat (even if it is just a moment of turning inward during the day) I see that my own attention was weak, just a kind of dim, flickering light, but I am always certain that if I just keep following it, leaving the known world of my thinking for the unknown, I may come upon wonders. In such a moment, I begin to grasp something that the great spiritual traditions teach, that we and our ancestors all the way back to the beginning of humanity are one. They exist in us. We resonate with the same rhythms: the day and night, the heartbeat, the breathing. And some of us we have another possibility also, to resonate with the laws under reality, to be the eye that reflects the Whole.

The Ascetic at the End of the Bar

August 18, 2011 § 15 Comments

In college I read a book that was modeled on Dante’s Inferno. Charting the progress of a young African American man through various American cities, the tale made the point that we have rings of hell right here and right now, and that we have our own poets and storytellers (Dante travelled with Virgil) to bear witness. By now (thanks to the lectures I listen to in my car) I realize that Dante was radical himself, filing his tale with bold examples of corrupt popes and officials but the image from that masterpiece that stays lodged in my aging brain is the image of the deepest ring of hell and Satan frozen, utterly incapable of movement. The idea that evil was being outside the flow of life and that freedom had to do with being in alignment or obedience to the higher laws of life—freedom as obedience–this was a huge paradoxical news flash. But I intuitively knew it was true; think of addiction, think of dreary nowhereness of life on the lam.

What stayed lodged in my heart and mind from the modern urban inferno was an image of a young black man sitting in a rough bar, playing the tough guy, harboring a secret asceticism under his ragged coat. I was a dreamy white girl from the sticks and I identified with him!

I realize now that I have treated having a spiritual like being in a rough bar. Picture the bar in Star Wars or any other archetypal rough bar, full of strange characters. My sense of having a spiritual life was that it was best lived as a kind of secret agent—outside seeking to be a woman of the world, learning things go, finding a place, a craft, then being a worker among workers; while inside seeking truth, exploring what it might mean to be in alignment with higher laws. The sense that having a spiritual search was best kept under wraps was born of a sense of how quickly consciousness gives up its freedom, attaches itself to images, memories, thoughts—especially thoughts about self. I was wary of identifying with a spiritual path, of assuming the role of follower or teacher of any particular way, because even as beginner (especially then) it was easy to see how people lost the openness of beginner’s mind as they identified with a role. It seemed to me that it was best to live a double live, to be a kind of secret agent of transformation. I longed to know a greater life, a life that I felt certain was lived by other beings in other times. But I didn’t want to deceive myself, to lose the life I was seeking by grasping at it.

It took a long time and many experiences of loss and gain to realize that we find the path to freedom in those moments (really, in moments) when all separation falls away. Almost everyone has had a few “if I get out of this alive” moments. In those moments, for me at least, there is no more inside and outside, no self and others. There is just the understanding that life is fleeting, burning–it really is an inferno! There is no time in such a moment to care about who we are–there is just a wish to join in and be helpful, to be one more pair of hands on the bucket (or broom or sandbag or feeding) brigade. Separation is hell, and there is a way out.

She Teaches the Torches to Burn Bright

August 15, 2011 § 3 Comments

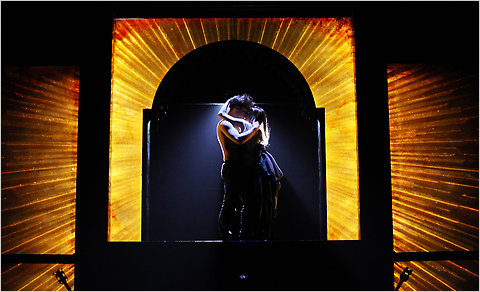

Unexpectedly and at short notice (which is the best way to do many things), a friend invited me to see “Romeo and Juliet” performed by members of the Royal Shakespeare Company at the Park Avenue Armory, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. From the moment I filed into the cavernous Drill Hall, I felt I was participating–not just passively observing but actively engaging–in something very special. I climbed winding stairs to a tier overlooking a stage in a replica of its main theater in Stratford-Upon-Avon–shipped from England in 46 shipping containers (“Millimeter for millimeter, it’s pretty much the same as what we’ve built in Stratford,” said Michael Boyd, artistic director of the RSC, told a New York journalist). Surrounded by beautifully dressed people (one young woman nearby wore a dress that seemed to be made of silken white petals and sky-high white heels) I witnessed a drama that was more than a spectacle in space: what unfolded was an event that reminded me that human lives can contain moments of “timeless time. ”

The Yale professor and author Harold Bloom teaches that there is no greater portrait in the Western tradition of literature of a woman in love than Juliet. Her constant generosity is a model of the utmost capacity of the human heart to hold and give a force, an intelligence beyond what we humans know as feeling. In describing Juliet, Bloom quotes the modern philosopher Wittgenstein, who came up with this aphorism: “Love is not a feeling. Love is put to the test, pain not. One does not say: ‘That was not a true pain, or it would not have passed away so quickly.'”

This RSC production put Romeo and Juliet in slouchy, sloppy modern dress while all around them are players in Elizabethan garb. This decision underscores the way Shakespeare smashes stereotypes and explodes easy summations. He took a well-known story about the rebellious impulsiveness of youth and made it a celebration of the possibility of transcendence in the midst of lives doomed by the mechanical turning of many wheels. He put into the mouth of a 14-year-old girl lines of extraordinary wisdom and beauty; and he showed how Romeo’s very being was changed by her capacity for love. “My bounty is as boundless as the sea, my love as deep; the more I give to thee, the more I have, for both are infinite.” I left out the customary slash marks and capitalizations so you might better appreciate the insight under the poetry. She understood what it might mean to enter the timeless.

Naturally, the New York critics had any number of things to say about this production and I agreed with some of what they said–I too wanted the transforming purity of Juliet’s love to rise up and be a still point in the turning world. And yet the RCS production came at just the right moment for me, a “teachable moment.” Flames and smoke shot up when the Montagues and the Capulets circled one another in the heat and passion of anger; flames and smoke shot up when the men and women at the Capulet’s masked ball circled one in a courtship dance–while powerful drum-driven music evoked the playing out of inexorable laws of nature, of blood and tribal loyalty. And in the midst of it, something brighter than fire, a timeless moments of clarity, of love. There I was, heavy-hearted about the riots in England and the seeming hopelessness of the way things are going here and here in the midst of the doom and gloom–and in an American armory of all places–were 41 English players and the Globe itself unfolding this timeless event–the opening to true love. I remembered that such a moment can change a life. I remembered why Shakespeare stays fresh and why his work calls people to make such extraordinary efforts.

“The path of all buddhas and ancestors arises before the first forms emerge; it cannot be spoken of using conventional views.” Translated from the great Zen master Dogen’s Treasury of the True Dharma Eye by Kazuaki Tanahashi, this mysterious line appears in the current “Seeing” issue of Parabola. Reading this line late at night after “Romeo and Juliet,” I felt certain that there always is hope for us, always a higher source of wisdom and compassion, and that Shakespeare knew this. In his introduction in Parabola, Tanahashi explains Dogen uses the word “dream” to describe enlightenment. Shakespeare knew how to dream.